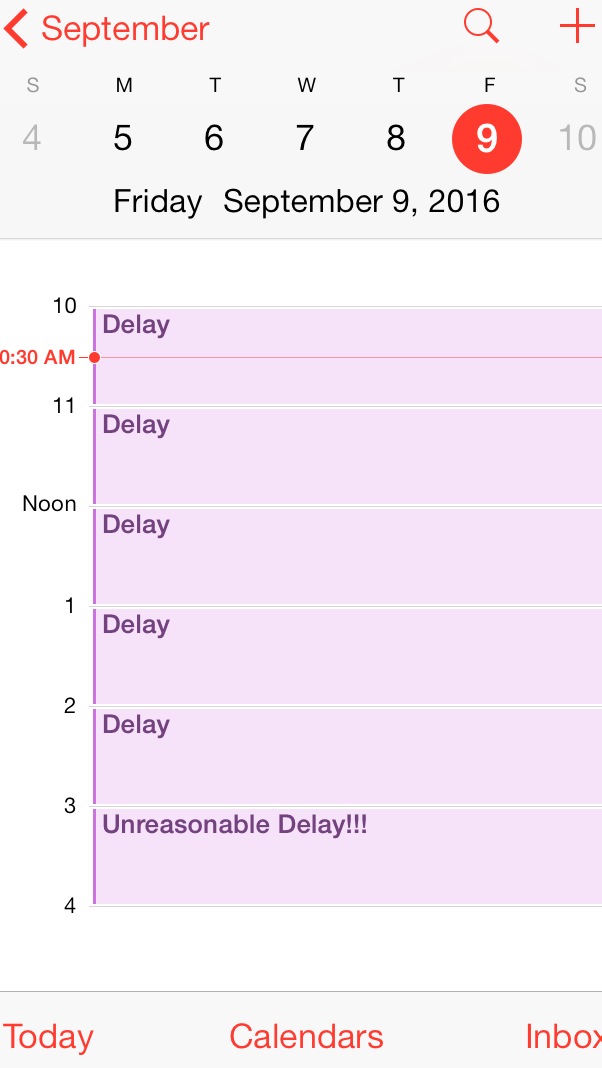

Its no secret that delay has become a very big topic, and one of great contention, in the criminal legal landscape. For years crown and defense lawyers have voiced their concerns over the impact that delay has had on the pursuit of justice. Defense lawyers arguing their clients cannot get on with their lives until their case has been dealt with (many papers have dealt with this issue finding that the anxiety accused people live with can cause great harm); and crown lawyers arguing limited resources are to blame. Some delay is inevitable – the complexity of criminal cases has been rising for sometime, while the funding to prosecute these cases has not kept up with the sheer numbers that are being brought before the courts – but when does this delay become so unreasonable that it warrants a response from the courts?

Section 11 (b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms provides that: “Any person charged with an offence has the right…(b) to be tried within a reasonable time”. Section 11 (b) can, in essence, be taken to provide a right to a speedy trial.

For years the doctrine of unreasonable delay was governed by a case that came out in 1992. The case in question, R v Morin [1992] 1 S.C.P. 771, set out the framework for applying s. 11 (b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A recent Supreme Court of Canada decision has changed this framework where the court found that the old framework from Morin was too “unpredictable, confusing, and complex, and it ultimately contributed to the delays that it was trying to prevent. It has itself become a burden on an already over-burdened trial courts”.

In R. v. Jordan [2016] SCC 27, the Supreme Court of Canada recently made broad and sweeping changes to the framework that determines whether an accused has been tried within a reasonable time under s. 11(b) of the Charter. These changes came from a 5-4 majority in favour of making changes to the previous framework. The new framework, in the words of the majority, is “intended to focus the s. 11(b) analysis on the issues that matter and encourage all participants in the criminal justice system to cooperate in achieving reasonably prompt justice, with a view to fulfilling s. 11(b)’s important objectives”.

The Presumptive Ceiling:

There is now a presumptive ceiling when looking at if the delay was unreasonable. When talking of the presumptive ceiling, the majority stated:

- there is a presumptive ceiling of 18 months on the length of a criminal case in provincial courts, from the charge to the end of trial.

- there is a presumptive ceiling of 30 months on criminal cases in superior courts, or cases tried in provincial courts after a preliminary inquiry.

- delay that is attributable to, or waived by, the defense does not count toward the presumptive ceiling.

- institutional delay that is not the fault of the Crown does count toward the presumptive ceiling.

Presumptive Ceiling Exceeded:

When the ceiling has been exceeded it is automatically presumed that the delay was unreasonable. The burden is then on the crown to show that either:

- a discrete event occurred that was reasonably unforeseen and reasonably unavoidable (delay attributable to such an event is subtracted from the total delay); OR

- the case was particularly complex in that the nature of the evidence or the nature of the issues required an inordinate amount of trial time or preparation time.

If the crown is unable to rebut the presumption that the delay was unreasonable, then the charges against the accused will be stayed.

Below the Ceiling:

Where the presumptive ceiling has not been exceeded, an accused may still show the court that the delay was unreasonable by proving that:

- it made a sustained effort to expedite the proceedings; and

- the case took markedly longer than it reasonably should have.

Where the accused establishes both of these elements, the charges against the accused will be stayed.

Since this decision from R v Jordan is new, it is really unclear exactly how the new framework for section 11(b) will protect the right to trial within a reasonable time. One thing is certain from this decision, and that is the Supreme Court of Canada has decided to not sit idly by when looking at the problem that is unreasonable delay. It has decided to do something. Time will tell how effective this will be.